This week, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released gripping new data on food insecurity among students in higher education. The report provides a detailed look at the number of college students experiencing food insecurity and how many students are accessing the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the nation’s largest and most successful anti-hunger program.

The GAO report was requested by hunger champions on Capitol Hill, Representatives Bobby Scott (D-Va.) and David Scott (D-GA), who are ranking members of the House Committee on Education and Workforce and House Agriculture Committee respectively. It is the first of two GAO reports responding to their inquiry–a second is expected later this fall–and updates a landmark 2018 study of student food insecurity.

Unfortunately, the data in many ways confirm what we know: rates of food insecurity are unacceptably high across the country, particularly among marginalized populations and students attending underserved and underfunded institutions. But it provides powerful new insights into this crisis. Using nationally representative data from the U.S. Department of Education, the GAO estimates that:

- 3.8 million undergraduate students (23% of students) experienced food insecurity in 2020.

- Food insecurity rates are far higher among students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities and other Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs). In particular, nearly 4-in-10 (38%) of students at HBCUs were food insecure, compared to an estimated 20 percent at non-MSI institutions. For-profit college students also had exceptionally high rates of food insecurity.

- Students experiencing homelessness, genderqueer or gender nonconforming students, first-generation students, and older students (those age 24 or older) were among populations who experienced food insecurity at disproportionate rates.

These data are consistent with The Hope Center's analysis of federal data last year. However, the GAO report provides an updated and additional glimpse into the extent to which students are unable to enroll in SNAP. For years, advocates have sounded the alarm on the overcomplicated, inequitable, and broken student eligibility rules within SNAP. Students in higher education must not only meet the regular income, citizenship, and other criteria to be considered eligible for SNAP, but they also must jump through additional hoops, usually by working 20 hours per week on top of a full-time course load, caring for a dependent child, or having a disability, to access the same aid.

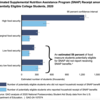

For the first time, we see the results of these complex and burdensome requirements, and they are sobering. The GAO estimates that just 3.3 million college students were potentially eligible for SNAP benefits in 2020. These were students with household incomes below 130% of the federal poverty level who also met one of the complicated student SNAP exemptions through things like working 20 hours weekly, caring for a dependent child, or having a disability.

Of those 3.3 million potentially eligible students, 2.2 million students (67%) reported that their household did not receive any SNAP benefits. In other words, two-thirds of students who likely meet the stringent eligibility criteria for the SNAP program are not benefitting from the program. By comparison, just 18% of all U.S. households who are eligible for SNAP don’t receive it (reflecting an 82% participation rate). Therefore, student SNAP uptake is nearly four times worse than the general population.

The problem may be even more dire than GAO calculated: the underlying federal data only indicates household receipt of SNAP, but there is no federal data to indicate that students themselves are receiving benefits, as opposed to a family member or someone they live with.

GAO calculates that 1.1 million students could be receiving SNAP. But if a significant number of students’ family members are included in that total, the true number of student recipients may be lower than 1.1 million.

And in some states, families making up to 200% of the poverty level are eligible for SNAP, meaning there would more than 3.3 million students potentially eligible for SNAP (a larger denominator) but with the same number of recipients that GAO calculated, leading to an even lower uptake rate than the anemic 33% rate of eligible students getting benefits that GAO has calculated.

Further, the GAO report demonstrated the shortcomings in SNAP’s ability to reach students struggling with food insecurity. Among those who were potentially eligible for SNAP, a full 59% who also reported experiencing food insecurity did not report that their household received benefits (see figure below).

These numbers speak to the fundamental failures of the SNAP eligibility rules and enrollment process. SNAP’s student criteria are based on a failed understanding of the student population, and are predicated on the mistaken assumption that college students are a privileged group that can rely on parental or family financial support while in college. For students already navigating a complicated and insufficient federal financial aid system, the additional bureaucracy created by SNAP can be enough to keep them from getting support which can be the difference between staying enrolled and dropping out.

For students who are able to navigate the red tape, exemptions like the 20 hour work rule are also at odds with common sense and the evidence we have about student success: expecting students to work long hours on top of their course and academic requirements reduces their likelihood of graduating. Food-insecure students are often placed in a double bind that requires them to reduce their chance of graduating through an overloaded schedule in order to receive benefits that would otherwise help them graduate. Worse, some of the populations who could bypass the work rule – such as parenting students who could qualify by having a dependent of their own – have distressingly low enrollment rates. For example, nearly 40% of potentially eligible single parents do not report receiving benefits.

The GAO report also shines light on the failures of our financial aid and higher education financing system to meet students’ needs. An estimated three-quarters (76%) of students who were potentially eligible for SNAP also received a Pell Grant, which is unsurprising given that the Pell Grant is targeted toward students with low incomes. Yet, among students who received a Pell Grant, an estimated 31% reported experiencing food insecurity, higher than the average among all students.

For Congress, as well as state lawmakers and institutional leaders, there are clear next steps. Given the extraordinary gap between potential SNAP eligibility and actual enrollment, leaders across our higher education system must prioritize:

- Expanding enrollment through better outreach, cross-campus coordination, data-sharing, and other efforts to ensure that every student who may be eligible for benefits knows who to enroll and retain access. It should be a priority of every leader invested in the success of our students that those students are receiving the support to which they are entitled.

- Collecting and reporting regular, disaggregated data on the extent of the food insecurity and basic needs crisis, as well as updates on SNAP student enrollment. It’s important to remember that this data is a snapshot; having consistent data will allow leaders to prioritize specific populations of students and build evidence around what works to connect students with SNAP and other benefits. Congress should require that state SNAP agencies collect data on the number of SNAP recipients that are currently enrolled in higher education, in order to improve outreach and enrollment.

Most importantly, this data also makes clear that the SNAP student rules need fundamental reform. Given that 1-in-4 undergraduates cannot count on having enough food to eat, federal policymakers should finally do away with the false notion that students are well-off and do not deserve support. This analysis also shows that only a fraction of students (2-in-5) facing food insecurity likely meet the criteria to be eligible for SNAP, meaning there is substantial room to reform the program’s eligibility criteria so the populations that are most likely to experience hunger have access to benefits. The scope of student eligibility problems is a clear indication that the SNAP student rules themselves are an administrative burden that keeps students from being able to understand the program, complete paperwork and verification requirements, and manage the enrollment process. Simply increasing outreach to students about a wildly-complex benefit program will never be sufficient to close the “SNAP gap.”

Furthermore, a benefit that the vast majority of potential recipients cannot access simply amounts to false hope. Forcing low-income, food-insecure students to jump over additional hurdles has resulted in a worst-of-both-worlds situation: some students experiencing hunger are not eligible, while those who are eligible cannot reliably obtain support. As discussions over the Farm Bill reauthorization continue, it is clear that Congress must finally overhaul and simplify SNAP eligibility rules. Policy options include:

- Treat higher education as work by allowing enrollment in higher education to satisfy SNAP activity and participation requirements, which would remove the “work for food” dynamic that the program currently fosters and put students with low incomes on equal footing with other individuals who are eligible for SNAP.

- Streamline the overcomplicated exemptions that, data now firmly show, do little to help food-insecure students. Congress should ensure that students who are most likely to experience hunger, including Pell Grant recipients, independent students, all parenting students, clearly qualify if they meet the regular SNAP eligibility criteria.

Reforming SNAP eligibility will reduce bureaucracy and red tape for students and institutions, in addition to boosting student well-being and success. It should be a bipartisan and baseline principle that all students who are at high risk of food insecurity are able to seamlessly qualify for benefits. It’s time for lawmakers to put that principle into action.