Introduction

College students experiencing food insecurity can get help to purchase groceries through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as “food stamps.” There is a significant need for this food assistance. The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice conducted a national survey of college students in the fall of 2020 (“the Hope survey”), which found that more than one in three students do not have enough to eat. Today, students and their families are also struggling with higher food costs because of recent inflation.

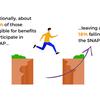

SNAP provides significant financial assistance to alleviate food insecurity, but many people who qualify for the program do not enroll. The “SNAP gap” refers to the difference between the number of people eligible for SNAP and the number actively receiving benefits. Nationally, about 82% of all people eligible for benefits under federal income and asset rules participate in SNAP, leaving about 18% falling into the SNAP gap.

Unfortunately, policymakers have enacted strict limits on student eligibility for SNAP, likely exacerbating the high rates of food insecurity and creating a wide SNAP gap for college students. During the 1970s, Congress adopted rules on SNAP eligibility to exclude many college students. Some members of Congress considered college students to be experiencing only a temporary loss of income or otherwise deemed students undeserving of food assistance. They were mistaken. As data on student basic needs insecurity has become more widely available and student demographics shifted, a clearer picture of pervasive economic hardship in college emerged. The National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health recently released by the White House describes SNAP rules for college students as “out of date given the current population who seek higher education credentials, many of whom are older, have low income, and hold caregiving responsibilities.”

Congress has created exemptions to restrictive SNAP eligibility that now allow some college students to qualify for benefits. While these exemptions somewhat broadened access to SNAP, they also added significant complexity to a program that already contained a dizzying maze of eligibility rules and application processes.

Closing the “college SNAP gap” by enrolling students who are potentially eligible for SNAP into the program—even amidst tight eligibility rules—is key to relieving widespread food insecurity among college students.

Due to federal limitations on collecting student-level data, it is not currently possible to identify the precise number of college students falling into the national SNAP gap of 18%. Still, several relevant data points suggest the SNAP gap is much wider for college students than for the general population.

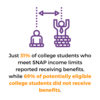

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report in 2018 analyzing federal student survey data. GAO found that just 31% of college students who meet SNAP income limits reported receiving benefits, while 69% of potentially eligible college students did not receive benefit.[1] GAO also examined data on potentially eligible students with at least one “risk factor” for food insecurity and found that SNAP only served about 43% of such students with at least one risk factor, while 57% of at-risk students were not receiving SNAP benefits.[2] A report by Young Invincibles estimates that just 18% of college students are eligible for SNAP and only three percent actually receive benefits, leaving billions of dollars per year on the table.

Only a few states collect data on student enrollment in SNAP. Two have identified a significant college SNAP gap. In Virginia, only 11% of likely income-eligible undergraduates were enrolled in SNAP in the fall of 2019, representing just three percent of all undergraduates.[3] And in California, after a concerted outreach campaign, just over 10% of the state’s community college students were enrolled in SNAP in 2019-20.

Far more college students are eligible for SNAP than they or the college staff who serve them may realize. And a much broader population of students is eligible for SNAP for the remainder of the COVID-19 public health emergency due to the temporary flexibilities passed by Congress. Local and state agencies, institutions of higher education, and community-based organizations should collaborate to reach students and help them enroll in SNAP—and many are already doing so.

This brief cuts through the fog of complexity that surrounds SNAP eligibility for college students and provides a road map for states and colleges to broaden SNAP eligibility and strengthen outreach to students about this critical yet underutilized food assistance.

Other Hope Center resources on SNAP access

The Hope Center has extensively researched SNAP eligibility and outreach over the years, providing a number of helpful resources:

- States Leading the Way in SNAP Eligibility and SNAP Outreach To Students offers best-practice examples of states that have creatively identified opportunities to make SNAP more accessible to students.

- Best Kept Secrets explores the temporary expansion of SNAP eligibility established by Congress and identifies states that could be doing more to promote this eligibility expansion.

- The Hope Center's most recent national student survey provides a wealth of insights on food insecurity and benefits access.

Why SNAP Matters

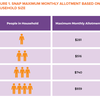

SNAP is the leading federal program for reducing food insecurity. Its efficacy is not rocket science: students who don’t have to worry about whether they can afford to eat can focus more effectively on their studies. SNAP participation can provide that peace of mind. A student enrolled as a single-person household could get $281 per month in groceries, or $3,372 per year (Figure 1).

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Amounts shown are for October 1, 2022 through September 30, 2023.

The connection between food security and student success is well-documented. Research has shown that food insecurity hurts academic performance.[4] Because SNAP participation reduces food insecurity, student enrollment in SNAP is associated with higher retention rates. Findings from a demonstration project that connected students from low-income backgrounds to public benefits showed that accessing SNAP and other public benefits can increase students’ financial stability and improve their likelihood of completing degrees or certificates. In a study conducted at a public university in California, enrolling in SNAP was associated with a significant boost in retention rates among students experiencing basic needs insecurity.

The College SNAP Gap

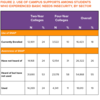

Unfortunately, few students experiencing food insecurity actually enroll in SNAP—or get any help in accessing the benefit. The Hope survey found that fewer than one in five (18%) students who reported experiencing basic needs insecurity were enrolled in SNAP, despite the potential for the program to alleviate that food insecurity (Figure 2). More than one in four (26%) students experiencing basic needs insecurity said they had not heard of SNAP at all, and more than half (55%) reported they had heard of SNAP but not used the benefit, reflecting significant opportunities to expand awareness of the program.

Source: The Hope Center Basic Needs Survey 2020.

As previously mentioned, GAO also examined the SNAP gap for college students. They found that, among 3.3 million students who were likely eligible for SNAP and had at least one risk factor for food insecurity, more than 1.8 million of them (57%) did not report receiving SNAP in 2016.

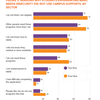

Students who are potentially eligible for SNAP face significant obstacles, including lack of knowledge about complex program requirements, stigma around applying for public benefits, and bureaucratic obstacles. The Hope survey asked students who were experiencing basic needs insecurity about their reasons for not using campus supports and public benefits, like SNAP and emergency aid. The vast majority of these students believed they were ineligible or that other students needed the resources more than they did (Figure 3). More than half said they did not know how to apply.

Source: The Hope Center Student Basic Needs Survey 2020.

Focus groups convened by Healthy CUNY at the City University of New York also found that “students who have applied for SNAP do not receive benefits because they experience poor treatment at the [county assistance office], become discouraged, and give up on trying.”[5]

How Students Qualify for SNAP

To qualify for SNAP, students must meet the income requirements that apply to everyone participating in the program and eligibility requirements specific to students. Although SNAP is funded by the federal government, states are primarily responsible for administering the program and have discretion in how they interpret certain federal requirements and the income limits in their state. The result is often a confusing maze of eligibility that can pose a significant barrier to enrolling eligible college students.

Federal SNAP rules require recipients’ “household” income to fall below a monthly “gross income threshold” set by the state within certain federal limits. However, federal law specifies who is included for the purposes of “household” income, which generally includes all individuals who live and purchase food together. [6] Young adults ages 18-21 who live with their parent(s) can only apply as part of their parent(s)’ household, but individuals aged 22 or older may be eligible to apply on their own. These SNAP rules differ from how federal financial aid determines whether a student is independent.

At the time of publication, 19 states and the District of Columbia set the gross income threshold for SNAP at the federally allowed maximum of 200% of the federal poverty level. In calendar year 2022, that maximum income amount is $27,180 per year for an individual and $46,060 per year for a family of three. [7] Seven states use a lower threshold of 185% of the federal poverty level—which cuts the number of people eligible for SNAP—and other states have even lower income thresholds. It is also an option for states to impose an “asset” test to exclude individuals from SNAP. While most states have elected a federal option to waive the SNAP asset test, five states limit the amount of personal assets—like the money in a bank account—that a household can possess.

Federal law significantly limits SNAP eligibility for students, contributing to the widespread misunderstanding that college students are ineligible for SNAP.[8] The federal government should lift these limitations on students. In fact, current exemptions available for college students could allow millions of potentially eligible students to qualify for benefits.

Most students are only eligible for SNAP from the first criteria—working an average of 20 hours or more per week. However, this work requirement is counterproductive to student success because it distracts students from their primary responsibility to attend class, study, and graduate. Research shows that working more than 15 hours per week can negatively affect college completion. The recently released White House National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health notes that “SNAP’s college student eligibility restrictions are out of date given the current population who seek higher education credentials, many of whom are older, have low income, and hold caregiving responsibilities. ”

During the COVID-19 public health emergency, Congress has created an important new route for student eligibility. Students with a $0 Expected Financial Contribution (EFC) or who are eligible for federal or state work-study can qualify for SNAP without work requirements. This opens up SNAP eligibility for many more students than ever before—possibly to an additional three million students. This expanded eligibility window will close when the federal government declares an end to the public health emergency associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The federal government can help by extending these flexibilities for as long as possible and addressing student eligibility during the next reauthorization of the farm bill, which sets SNAP eligibility rules.

The federal government has granted states considerable flexibility in interpreting the SNAP student rules, offering students in some states more opportunities to qualify for SNAP without meeting the work requirement. States can also streamline the confusing maze of eligibility exemptions and close the SNAP gap. All state SNAP agencies and state legislatures should review their regulations and statutes to identify opportunities to expand SNAP access to college students. Agencies may find it helpful to consult with state higher education agencies and rehabilitation commissions. Categories of students who could benefit from state efforts to interpret federal rules more flexibly include:

- Students in the vast majority of community college programs

- Students in career and technical education programs that receive Perkins Act funding

- Students at public colleges enrolled in programs of study that improve employability and predominantly serve students with low incomes, including career-focused programs at four-year colleges and programs serving graduate and professional students

- Students with disabilities recognized by a state vocational rehabilitation program or a college’s office of disability or accessibility

Keep reading for some useful examples of states taking these steps.

For more than a decade, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has taken a leading role in providing college students robust access to SNAP. The state’s Department of Transition Assistance (DTA) made key policy changes in 2009 to broadly interpret SNAP eligibility for college students and has expanded this policy in recent years to further support student participation in SNAP.

In 2009, DTA agency leadership agreed with an analysis of federal SNAP regulations by the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute (MLRI) proposing that students at public colleges that primarily serve students with low incomes—and who are enrolled in programs of study that generally increase students’ employability—should be eligible for SNAP participation.[11] Since community college programs of study generally serve students with low incomes and improve their employability, most community college students are potentially SNAP-eligible on their own, or as a member of a SNAP household—so long as those students are US citizens or eligible immigrants and they meet the gross and net income tests. In 2009, to streamline eligibility determinations, the agency empowered community college staff to determine whether a student’s course of study falls within the Perkins CTE exemption or if having the degree makes them more employable, rather than needing to identify a list of acceptable courses or seek prior approval from the state.

The 2009 DTA policy has been successful in establishing a straightforward process for determining student eligibility for SNAP. DTA and MLRI have also collaborated in conducting extensive outreach to students and college staff regarding the availability of SNAP to support students’ food security. SNAP enrollment data is unfortunately not available for college students in Massachusetts, but a broad consensus exists among advocates, state and county agency staff and higher education leadership that the state’s student SNAP policy has significantly increased the number of students who apply for and receive SNAP.

- Additionally, Massachusetts has determined that all community college students (in either associate or certificate programs) are enrolled in programs that are eligible for SNAP, and do not have to meet other exemptions as long as they meet the other SNAP requirements like income caps and citizenship. The state determined community college programs to be equivalent to SNAP E&T as they result in broad increases in students’ employability.

- Illinois, Michigan, New York, Oregon, and Pennsylvania have determined that many, if not most, community college students are eligible for SNAP if they are enrolled in career and technical programs, or are in other career-focused programs which lead to an increase in students’ employability.

- Several states have determined that students are SNAP-eligible if they participate in a program at a public college in which the college determines the student will be more employable with a certificate or associate degree. California passed a law in 2021 which offers SNAP eligibility to students in programs of study at all public colleges that have an employment-related component (such as internships, apprenticeships or seminars that teach resume-writing or other skills).

- Despite the pejorative and outdated phrasing in federal law, states have used their authority to define the federal “physically and mentally unfit” exemption to lift the work requirement from a broader group of students. Some states have allowed a wide range of health care professionals to certify that supplementing college attendance with compensated work is inadvisable based on the student’s mental or physical health conditions. For example, California authorizes a physician, nurse, psychologist, psychiatrist, or behavioral health case manager to make these determinations. Some states explicitly define students experiencing homelessness as “unfit” for work and, therefore, exempt from work requirements.[12]

- Some states have codified that students may be deemed SNAP-eligible if the student reasonably expects and foresees to be participating in a state or federal work-study program—even if the student has not yet been placed into a work-study position and or have yet to receive funds. Federal law allows students to be exempt from the 20-hour/week work requirement if they are “participating” in a work-study program. In these states, a student is eligible for the SNAP exemption up until the student is affirmatively denied work study.[13]

Communicate with students in plain and stigma-reducing language. Benefit application language is typically complex and laden with bureaucratic jargon. Students, like most applicants, struggle to understand the terminology, leading them to provide incorrect information and omit necessary documentation. In California, a study of statewide outreach to 285,000 students who were likely eligible for SNAP resulted in nearly 10,000 students applying for SNAP benefits within six weeks. These results are similar to a study of senior citizens who were twice as likely to enroll in SNAP if they received information by mail and three times as likely if they received information and phone-based assistance in enrolling.

Use financial aid data to reach or identify students for outreach. State agencies responsible for financial aid have access to information on students who have filed the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which can be used to identify and reach students who may be eligible for SNAP. The Massachusetts Secretary of Higher Education used this data to send a series of letters to students potentially eligible for SNAP due to the COVID-19 public health emergency. Notably, the Secretary told his own story of receiving SNAP benefits in college to relieve potential stigma among students who might consider applying. States can also provide assistance to colleges looking to utilize January 2022 federal guidance on FAFSA data-sharing.

Convene educational outreach coalitions. State higher education and human services agencies can build SNAP educational outreach coalitions with anti-hunger organizations and institutional leaders. The Ohio Department of Higher Education, for example, partnered with the Ohio Association of Food Banks, the Center for Community Solutions, and a wide spectrum of colleges and universities to get the message out about expanded access to SNAP due to the COVID-19 public health emergency. The coalition convened a webinar, briefed financial aid and student affairs staff, disseminated fliers and other collateral to institutions and students, and conducted a detailed survey on SNAP education and outreach at the institutional level.

Develop and make available outreach resources for institutional use. State higher education and human services agencies have the expertise and resources to provide informational resources that colleges can use or adapt for their education and outreach activities to students. In New York, the state SNAP outreach partner, Hunger Solutions, created fliers for distribution to students.

Designate higher education liaisons. Student eligibility for SNAP is complex, making it hard for college leadership and staff to give students appropriate guidance on applying for benefits. State and county human services agencies should designate higher education liaisons to collaborate with state higher education executive offices and to provide guidance to colleges and community-based organizations. In California, county agency liaisons are highly valued by college leadership and staff.

While states have a responsibility to maximize SNAP flexibility for students, colleges can also help connect more students with low incomes to SNAP and close the SNAP gap. Colleges can address major obstacles to SNAP enrollment of potentially eligible students: lack of knowledge of the benefit, confusion over program eligibility requirements, and stigma around applying for public benefits.

Under federal law and guidance, colleges can use data from the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) to identify students who are potentially eligible for SNAP—and other public and tax benefits—and conduct targeted outreach to these students to help them apply. For example, college financial aid offices can use their FAFSA and other administrative data to:

- Identify which students may meet SNAP income limits based on their family’s adjusted gross income listed on the FAFSA;

- Of students identified in step #1, further identify which students are either:

- Group A: Exempt from the SNAP work requirement based on:

- Receipt of state or federal work-study

- Eligibility for work-study (during the public health emergency)

- Having a $0 EFC (during the public health emergency)

- Being a parenting student or independent student with dependents; or

- Being enrolled in a program equivalent to SNAP E&T as determined by the college or state interpretation of federal regulations; or

- Group B: Can qualify for SNAP by working 20 hours per week

- Group A: Exempt from the SNAP work requirement based on:

- Then, send out customized emails, texts, and postcards to students likely eligible for SNAP to let them know students like them may be eligible for financial help with groceries.

For example, students in “Group A” have the easiest path to enrolling in SNAP and can receive messages that communicate they may already be eligible to receive benefits. Communications to Group B could mention students may be eligible if they are currently working part-time or more.

Colleges can also consult with the state or local government(s) for assistance in determining student eligibility for SNAP. In California, a new state law requires public colleges to use FAFSA data to identify students who meet the income requirements of SNAP and to conduct email outreach to these students that includes contact information for the local county welfare agency that can help them enroll in benefits.

Build knowledge through…

The college can send students text messages about potential eligibility for SNAP benefits. Three Hope Center studies on text messaging found that texts could significantly improve student take-up of emergency aid, improve the rate at which students use services, and increase their awareness of public benefits. Like the outreach in California, colleges can improve response rates to their communications by customizing communications based on student exemption categories, including language that suggests students will be eligible, and ensuring outreach is simple, easy to understand, and occurs in multiple formats (i.e., email, text, and postcard). For example, Cal State Chico created a campus and social media toolkit on SNAP.

A campus webpage on basic needs resources is a powerful tool that can raise awareness of existing resources and connect students to those resources. College staff and volunteers should work to group resources by type, including public benefits and referrals to community resources, indicate eligibility criteria and restrictions, and outline how to access the support. Language should communicate caring and relieve stigma.

Student affairs staff, especially those in direct contact with students and responsible for managing academic support programs, can help close the SNAP gap by sharing information with the students they serve. The most cost-effective approach is to centralize student support. Basic needs centers consolidate existing campus-level interventions with assistance in applying for public benefits, referrals to community social services, access to emergency aid, and other comprehensive supports bundled in a single on-campus location. These centers directly strengthen students’ ecosystem of supports, provide assistance in identifying and applying for public benefits, and facilitate effective referrals to internal services and resources in the community.

Faculty members interact closely with students on a daily basis, making their role in basic needs security a vital one. Institutions should establish a basic needs task force and faculty should play a prominent role.Faculty can also provide direct support by adding a statement on basic needs insecurity on their course, helping to connect students to resources on campus. Syllabi statements can alert students to potential eligibility for SNAP and identify a campus office or website where they can obtain more information.

Reduce stigma by…

Many students resist being thought of–or thinking of themselves– as in need of government benefits. It is essential to avoid framing that stigmatizes students or implies victimhood or neediness. Faculty, institutional leaders, and staff should receive professional development on using language that normalizes the experience of accessing basic needs resources. Phrases that alleviate stigma include:

- “We know money is tight for most students.”

- “We want to help you focus on studying and make progress toward your goals.”

- “Do you need help affording groceries this month? We can help!”

- “There are enough benefits for everyone.”

Overcome bureaucratic obstacles by…

Colleges can employ staff who serve as a liaison with government agencies and community-based organizations and develop expertise in determining eligibility for public benefits. The reach of a benefits navigator can be expanded by training students to provide peer-to-peer counseling in reviewing eligibility and navigating benefit application systems. California and Oregon fund staff who work directly with students in benefit navigation. In New York City, CUNY trains and supports students to become “Food Security Advocates”who provide information and assistance to their peers about SNAP and other cash assistance. Colleges can also establish partnerships with non-profit organizations doing benefits access, such as GetCalFresh in California or BenePhilly in Philadelphia, or collaborate with local organizations that may be interested in this work.

Determining student eligibility may seem complex to public agency or student affairs staff, but colleges can provide simple pre-screening tools for students to find out if they might be eligible for SNAP. The City University of New York (CUNY) has created such a system that enables students to look up their eligibility based on key criteria, print out the relevant document, and attach it to their application. This accelerates and simplifies the eligibility process. Fresno State University offers an interest form on its student portal that allows students to schedule an appointment to review their eligibility for SNAP. Finally, many colleges maintain contracts with Single Stop USA, which uses technology to screen students for a variety of public benefits, including SNAP, and helps get them enrolled.

Colleges can work with state or county SNAP agencies to refer students directly to enrollment in SNAP benefits with a student’s permission. For example, Compton College in California has a data-sharing agreement with the Los Angeles County Department of Social Services in which the institution sends student data to the agency, and the agency responds with an assessment of SNAP eligibility.[14] State or county agencies may also be willing to conduct outreach and enrollment at the institution.

Conclusion

SNAP is a valuable public benefit shown to reduce food insecurity that undermines academic performance and students’ well-being. Program benefits are fully financed by the federal government, and many private funders have expressed interest in supporting benefit navigation initiatives that boost SNAP enrollment. Working together, institutions of higher education, states, and community organizations can close the college SNAP gap and build an effective basic needs ecosystem around students so that they can focus on their academic success. Students deserve nothing less.

[1] Author calculations from Government Accountability Office (2019). “Food Insecurity: Better Information Could Help Eligible College Students Access Federal Food Assistance Benefits.” Table 1, Page 16. GAO notes that, in the GAO analysis of 2016 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2,257,121 students report receiving SNAP out of 7,339,571 total students with household income at or below 130%of the federal poverty level (30.75%).

[2] Supra. Figure 2, Page 19.

[3] Authors calculations based on data provided by the State Council of Higher Education of Virginia (2022). Undergraduate Fall Enrollment, SNAP Participation and Potential Eligibility.

[4] Patton-Lopez, M., et al (2014). “Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among students attending a midsize rural university in Oregon.” 46(3): 209-214. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

[5] Healthy CUNY and the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. The State of Food Security at CUNY in 2020. CUNY School of Public Health and Health Policy, April 2020.

[6] Gross income includes the household’s unearned and earned income before any taxes or payroll deductions. Some income, such as federal financial aid and VISTA payments, does not count.

[7] Note: Federal poverty levels can be accessed at: https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/federal-poverty-level-fpl. In 2022, 200% of the federal poverty level is equivalent to $54,500 for a family of four, or $27,180 for a one-person household.

[8] Students enrolled in college less than part-time (as defined by the institution) are not treated as “students”, but may be subject to time limits and work rules if between the ages of 18 and 50.

[9] During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, students qualify for SNAP if they are deemed eligible for work-study but no funded slots are available or they have not yet received work-study funds.

[10] Granville, P. (October 29, 2020). Appendix B: Regulatory framework for proposal to broadly approve CCC programs for the employment and training program exemption. The Century Foundation.

[11] Burnside, A., Gilkesson, P., & Baker, P. (April 20231).Connecting community college students to SNAP: Lessons from states that have expanded SNAP access and minimized the “work for food” requirement. CLASP and Massachusetts Law Reform Institute.

[12] States that define students experiencing homelessness as unfit for work include Nevada, Minnesota, and Virginia.

[13] California Department of Social Services. (April 2, 2018). All-County Letter 18-27. Oregon Department of Human Services, Chapter 461, Division 135, 461-135-0570(3)(b)(A-D).

[14] Compton College (undated). Student authorization to share information between the Department of Social Services and Compton College to maximize CalFresh Benefits. https://compton.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_1XDfFOaxDGZeOk6