The four million parenting students in higher education represent some of the most powerful examples in American society of determination, persistence, and the dream of upward mobility. Yet for the one-in-five undergraduate students in college who are also caring for a dependent child, these dreams of a better life through education—for themselves and their families—can quickly run aground against the financial and logistical hurdles that can prevent them from affording and completing a degree program.

Despite the fact that over half work full-time while enrolled in classes, parenting students report higher rates of food insecurity, and single parents report higher rates of homelessness than their peers. Meanwhile, parenting students must contend with the often-rapid increase in housing costs, and child care costs that rival (and often dwarf) tuition and fees, while others must rely on the generosity and time of family members to help out so they can juggle work and school. Parenting students graduate with more debt than non-parenting students, putting their families’ financial future at risk. And, like parents and caregivers across the country, parenting students are exceedingly likely to experience extreme stress, isolation, and exhaustion, so much so that the U.S. Surgeon General last month released an advisory calling attention specifically to parental mental health and well-being. In short, parenting students face the same acute challenges as everyone else, but with specific and additional obstacles that can render them unable to persist through college.

Parents who decide to enroll or re-enroll in higher education are taking a leap of faith that the time, energy, and money that they’ll spend will result in a better life for themselves and their children. It is impossible to argue that putting the resources necessary to ensure the success of this specific population is unwarranted.

Mark Huelsman

Director of Policy and Advocacy, The Hope Center for Student Basic Needs

Many leaders, including Vice President Kamala Harris, have begun to center the need to invest in the care economy—including child care and early education—and build financial resiliency among parents and working-class families. Yet in recent years, lawmakers have not put nearly enough resources or attention toward meeting the needs of this unique population, particularly when it comes to ensuring that the dependents of parenting students are cared for and set up for success. Finding a reliable and affordable child care arrangement can be a constant struggle, and ensuring that one’s children have enough to eat each day can force students to work long hours, skip classes, avoid certain academic responsibilities, or face stress and anxiety that undoubtedly impact their studies. It is clear on nearly every measure that we must increase investments and resources to make higher education easier and more affordable, especially for those with children..

Unfortunately, federal policy is going in the wrong direction.

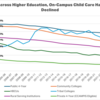

For colleges and universities, the resources required to maintain child care supports—including on-campus childcare centers—can be daunting. Amidst the rising cost to provide child care and stagnant or declining state support for higher education, our analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education reveals that there has been a decline in the number of campuses offering campus-based childcare over the last two decades.

Source: The Hope Center Calculations from the U.S. Department of Education Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS)

The decline in child care availability at public 4-year and community colleges is particularly alarming, given that public institutions enroll a large majority of students in higher ed. Yet these schools, and community colleges in particular, have faced tight budgets for decades despite serving students with high need. Several innovative partnerships have sprung up across the country, including a promising model spearheaded by the Association of Community College Trustees (ACCT) and the National Head Start Association, but more federal support is essential in order to ensure that any parent attending a community college (or other school) has access to reliable, quality care for their children.

The Child Care Access Means Parents in School (CCAMPIS) program remains the only program dedicated to campus child care, and is designed to provide child care for low-income parenting students either on campus or through a community partner. For those who are able to access it, CCAMPIS participation is associated with higher rates of retention and completion, and better academic performance. Yet, funding for CCAMPIS remains far below the actual need; one estimate suggests that only 1% of potentially eligible students are served, and an overview of CCAMPIS recipients also reveals an underrepresentation of rural-serving institutions as well.

Congress can and should do better. The CCAMPIS Reauthorization Act, introduced just last week, would expand funding for this program nearly seven-fold while helping connect parenting students with other benefits for which they may be eligible, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), housing, or health care supports. It would also improve data collection so we have a better understanding of where parenting students attend and what their level and scope of needs are in order to better tailor campus and public supports.

Congress’s decision to allow the CTC to expire threw five million children back into poverty at a time of rising food, housing, and other everyday prices.

Mark Huelsman

Director of Policy and Advocacy, The Hope Center for Student Basic Needs

Beyond child care, lawmakers can ease the burden on parenting students by reinvesting in proven supports for children and families. Namely, Congress should renew the expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC), which provided low-income parents with a monthly allowance and led to a record decline in child poverty across the country. Congress’s decision to allow the CTC to expire threw five million children back into poverty at a time of rising food, housing, and other everyday prices (not to mention increases in the cost of attending higher ed).

Simplifying access and reducing burdens to enrolling in public benefits would also help. As mentioned, parenting students face high rates of food insecurity, yet due to the confusing (and sometimes contradictory) rules in SNAP, many students do not apply for or receive benefits that could put food on the table. Ostensibly, low-income parenting students can access SNAP without the need to effectively work a full-time job, but rules are complicated and hard to understand. In addition to meeting income, citizenship and other requirements, and attending school more than half-time, there are three separate avenues (or “exemptions”) for parenting students to potentially meet the criteria for SNAP, including:

- Care for a child under the age of 6.

- Care for a child age 6 to 11 and lack the necessary child care enabling you to attend school and work 20 hours a week or participate in work study.

- Care of a child under 12 while a single-parent enrolled in college full-time.

This creates unnecessary complexity and ambiguity, making it hard to communicate eligibility to students and for students to remain enrolled in benefits. A simpler pathway to SNAP eligibility would be to include all parenting students as meeting an exemption. Better, Congress should pass the recently-introduced Student Food Security Act, which would create an exemption for all independent students and ensure other categories of students most likely to face food insecurity are able to access SNAP.

There are other crucial investments that could support all students struggling to meet their basic needs that would likely have a disproportionate impact on parenting students. Expanding emergency aid, pursuing rent and housing relief, and reducing the cost of attendance altogether would allow parenting students to take on less debt, work fewer hours, and have the peace of mind that following their dreams will not lead to financial hardship and ruin. Congress should boost funding through the appropriations process for CCAMPIS, the federal Basic Needs for Postsecondary Students grant, and other programs that can bridge the affordability and success gap for these students.

Parents who decide to enroll or re-enroll in higher education are taking a leap of faith that the time, energy, and money that they’ll spend will result in a better life for themselves and their children. It is impossible to argue that putting the resources necessary to ensure the success of this specific population is unwarranted.

This year marks the fourth time that Congress, on a bipartisan basis, has designated the month of September as “National Student Parent Month,” It is heartening that our nation’s lawmakers continue to recognize the importance of elevating the stories and experiences of this unique population. The next step is to ensure we’re finally meeting their needs.