Every year, millions of students and their families confront a complicated and sometimes maddening college financial aid process. They’re eagerly hoping to secure the grants, loans, and scholarships they need to afford the high price of higher education—either to enroll in the first place,or continue toward their degree. Many are navigating this confusing financial aid process right now.

Despite the best efforts of so many exhausted staff in the financial aid offices of colleges across the country, these dedicated professionals rarely have the resources at their disposal to adequately help all families with financial need. Even in the best of times, emails and phone calls mount, long lines in the financial aid office form, and available dollars always run short. They are also working within an overly complex system that continues to overwhelm the students who need the most help.

And this year, students and financial aid officers alike have also been worrying about the looming impact of devastating layoffs of hundreds of staff at the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid, just as recent FAFSA woes had started to subside.

States have stepped up their efforts to drive more financial aid to struggling students, but a wide range of state budget pressures, from Medicaid to transportation, make it hard for these investments to fully meet students’ vast needs in the wake of rising costs of living.

Despite these headwinds for higher education, a 2020 change to federal law could provide a much-needed boost to financial aid. For students and families that don’t make much money and are intimidated by the high cost of college, this new change modifies the formula that determines how much in grants, scholarships, and work-study a student might get.

It’s a simple number that didn’t exist before last year. As explained below, a new “negative Student Aid Index” number is empowering colleges and states to direct more of their scarce resources to the students who need it most.

First, let’s review the key steps of the college financial aid process:

Applying for Financial Aid: A student (and often a parent if the student is under 24 years old) applies for aid, typically through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). Some colleges or states may require or offer additional forms. These applications require financial information from the student to determine their ability to pay for college. The FAFSA collects data like income, assets, and family size.

Receiving a Student Aid Index (SAI): Once the FAFSA is submitted, the student will receive a number called the Student Aid Index (SAI) that helps determine how much financial assistance the student is eligible to receive. The lower the SAI, the more need-based aid a student generally receives. At most institutions, students with the lowest SAIs will receive the highest amount of need-based-financial aid—as they should. (Note: SAI replaced a former term, the “Expected Family Contribution,” or EFC, which served the same purpose).

Financial Aid Offer Letter: After the application is reviewed, colleges send out financial aid award letters to admitted students. These letters outline the types and amounts of aid the student is eligible for, including federal and state grants, scholarships, work-study opportunities, and loans. The offer will usually include a breakdown of the total cost of attendance, including tuition, fees, housing, food, transportation, and other basic needs.

Accepting and Adjusting the Offer: Once students have reviewed their financial aid offers, they will often compare them if enrolling for the first time, and will need to accept or decline the various components. This may include deciding whether to accept loan offers or work-study opportunities. If a student feels that the financial aid offer isn’t sufficient to cover their needs, they can often appeal the decision with the financial aid office, particularly if there has been a significant change in their financial circumstances.

For many decades, the second step of receiving the “Expected Family Contribution” – now the Student Aid Index – was itself an anxiety-inducing experience.

The term “Expected Family Contribution” (EFC), was a weighty and misleading phrase that implied an often-shocking sum of money that parent(s) were expected to contribute toward their student’s year in college. These expectations were often wildly out of step with what little savings, or spare income, a family was prepared to spend.

In truth, the EFC was only used as a scale, or index, of relative need between students. No single number describes a student or family’s financial obligation, and students can also cover remaining financial need for college through borrowing, working more, or seeking lower-cost alternatives like community colleges.

In 2020, with the FAFSA Simplification Act, Congress made a long-overdue change to rename the EFC to the Student Aid Index (SAI), more appropriately reflecting its role as a simple relative indicator, or index, of student needs. Congress also did something even more important with this new law which many researchers and advocates had long suggested—Congress allowed the SAI to go negative, rather than stopping at 0.

Before this change to federal law, the SAI/EFC had been limited to a floor of “0” under the premise that a student couldn’t be expected to contribute “less than zero” toward their college education. And, the cost of attendance was supposed to represent all they might possibly need to cover.

The lowest-income students need even more help than the typical financial aid package to put college within reach. This issue could be especially difficult if a college inaccurately estimates its cost of attendance.

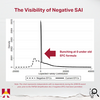

Since so many students from working families previously had a zero SAI/EFC, it had often been extremely difficult to determine how lower-middle-income students were different from those students with the very least financial resources. The federal formula was obscuring the full picture of student needs.

Source: Kelchen, R. (2020, August). Exploring Ways to Enhance FAFSA Efficiency: Examining the Distribution of Negative Expected Family Contributions. National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators.

In fact, more than a third (36%) of all students had an EFC of zero in 2019-20, according the most recent federal data. That’s millions of students with a zero EFC—about 6.1 million students, to be precise.

The SAI is now allowed to go negative to a maximum of -1,500, creating a new way to identify students who need the most help. By allowing the SAI to go negative, both students and colleges benefit.

A portion of the federal financial aid formula that protects working peoples’ income – known as the “Income Protection Allowance,” or IPA, has typically helped people without much income, such as the elderly, people with disabilities, those who had been unemployed or underemployed, and students themselves who had been (correctly) focusing on their studies and not earning income.

The IPA can now help students even more. Take, for example, a family who should have had $40,000 of their income “protected” for their basic expenses. If they only made $30,000 per year, they were missing out on the remaining $10,000 of income protection—while a family making more than $40,000 would get the full benefit. If more of a student’s family income is protected, their higher level of need is better reflected to colleges and states.

How the Math Works

| FORMULA | (Income) + (Assets) - (Allowances*) = (Adjusted Available Income) x (%) |

| OLD (EFC capped at 0) | ($40,000) + ($1,000) – ($44,000) = -$3,000 x (22%) = |

| NEW (SAI to -1500) | ($40,000) + ($1,000) – ($44,000) = -$3,000 x (22%) = -$660 |

| Note: Allowances refers to numbers that financial aid applicants can claim against their income, like the Income Protection Allowance. |

A negative SAI also allows colleges and states to have more visibility into which students need more help and to direct aid accordingly.

Source: U.S. Department of Education. (2024, March 21). 2024-25 Student Aid Index (SAI) and Pell Grant Eligibility Guide.

Why a Negative SAI Helps Target Scarce Financial Aid Dollars

We know that students and families are struggling with high college costs. According to The Hope Center’s Student Basic Needs Survey, three out of every five college students experience some form of food or housing insecurity while enrolled. This basic needs insecurity reduces their chances of graduating, entering the workforce, and supporting themselves and their families.

Students with the lowest incomes typically struggle the most with basic needs insecurity. Pell Grant recipients, parenting students, former foster youth, students with disabilities, and Black, Indigenous, and LGBTQIA+ students all report much lower wealth and much higher rates of basic needs challenges. Before, a 0 SAI and -1,500 SAI student appeared the same on paper, making it harder for a college to step in and help those students who most urgently needed financial support to succeed in college.

Think of it like an iceberg with most of its mass under water. When the SAI was capped at zero, it was harder to see any of the need students had below this waterline. With the negative SAI, we can see more of what exists below this waterline – about $1,500 more.

The transparency of the negative SAI allows colleges and states to identify and help students by better targeting their limited resources through their tools such as:

• Institutional grant and scholarship programs

• Emergency aid

• Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants (SEOG)

• Federal and state work-study aid positions

• State-funded grant programs

• Referrals to basic needs supports, like housing or food assistance

For example, a college that previously distributed its limited institutional grants to all students with a zero EFC might now decide to target a substantial portion of those funds toward students with a negative SAI (especially students with a -1,500 SAI).

Implications for Policy and Practice

As we speak, thousands of colleges across the country are constructing their financial aid packages for the students who will be on campus later this year, mostly starting in fall 2025. States are also convening at their capitols to budget for their financial aid programs over the next few years. Colleges and states should provide extra financial aid resources to the students with the lowest SAI numbers, down to -1500.

Colleges and states should also closely examine the data on their financial aid recipients each year to track enrollment, persistence, and completion trends. They can also supplement their awareness of students’ financial needs by surveying them regularly, such as with The Hope Center’s Student Basic Needs Survey, and identifying populations of students who may be particularly at-risk for stopping out. Surveys can be administered at the institution, system, and statewide levels.

The end goal is to help students afford their dreams of higher education. By targeting limited resources effectively, colleges and states can help put more degrees and credentials within reach for Americans who are seeking a path to opportunity through higher education and training.