While basic needs is a broad term that includes transportation, child care, mental healthcare, hygiene products, and more, this piece focuses on food and housing insecurity due to the availability of data.

Colleges were built around the assumption that students have families who are able to cover their living expenses. When students stopped fitting the traditional mold—young, white, wealthy, without dependents—that assumption proved glaringly inaccurate. Today, many college students aren’t just supporting themselves, they’re also helping their families make ends meet. But higher education is still built around an assumption that never accounted for them. This puts an enormous burden on students that tuition-based financial aid only partially relieves, leaving many students unable to afford their basic needs.

For the last four years, I’ve watched this play out as an undergraduate at the University of California, Los Angeles. While some of my friends and classmates don’t know where their next meal will come from, others take unpaid internships. While parenting students slip out of class early to pick up their kids, others stay late to talk with professors. While some students go to football games, others drop out with debt they can’t pay back. From graduation rates and academic performance to mental and physical health, basic needs security plays a massive role in student outcomes.

But students don’t hear about their basic needs during the admissions process. What students often hear about are financial aid packages and scholarships toward tuition costs, exclusively. There is a dramatic and harmful disconnect between colleges’ marketing to students and the reality of college life.

Students deserve the chance to accurately assess their financial options and choose the educational path that is best for them. In other words, students deserve to make informed enrollment decisions. For that to be possible, the admissions process needs to give students an accurate picture of college financial life. Specifically:

- Colleges need to acknowledge that financial aid alone will not always be enough to make ends meet,

- Students need to be aware of the circumstances in which financial aid is often insufficient, and

- Students need to be able to compare basic needs resources across colleges.

Potential students already know that it won’t be easy to afford college. It’s a driver of students' growing distrust of higher education. What students don’t know is that different schools provide different basic needs resources, or that basic needs resources even exist on campus. Informed enrollment is a chance for colleges to help students navigate the ongoing affordability crisis with clearer expectations.

The benefits of clear expectations should continue once students get to campus. Early communication could dramatically increase students’ awareness of basic needs resources. Moreover, this could help destigmatize food and housing insecurity. Early acknowledgment by colleges could help students understand that these issues are not personal failings and that they aren’t alone.

An honest look at my campus

The University of California, Los Angeles is one of the national leaders in supporting students’ basic needs. Our campus has full time positions dedicated to basic needs, well-organized and public survey data, and significant direct assistance for food, housing, transportation, and more. The same is true across the UC system. Additionally, there is a system-wide campaign for investment from the State and Federal Government. I developed much of this piece through conversations with passionate administrators in the UC system.

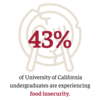

However, UCLA students are always surprised to learn that our school is a leader on basic needs. It doesn’t feel that way on campus: 35% of UCLA undergraduates continue to experience food insecurity.

Every weekday, students wait for the food pantry to open in a line that wraps around the corner and down the stairs. In the dorms—where students aren’t eligible for CalFresh and don’t have kitchens—many students choose a reduced meal plan to save money. The cheapest meal plan costs $5,000 for the academic year and gives students eleven meals a week, about one and a half meals a day. Even if students wake up hungry, some wait until right before lecture to eat so that they can focus.

Establishing who is responsible for addressing this problem is complicated. Currently, there is an incomplete patchwork of efforts from the Federal Government, state governments, colleges, private donors, and students. But colleges in particular need to better define their responsibility to students.

The UC’s basic needs response is maintained by $18.5 Million in State funding for food and housing insecurity. Students have called on the UC system to match the State’s investment, but campuses are hesitant to step in for a failing social safety net. Instead, the UC pursues new funding sources—lobbying the State Government, increasing CalFresh enrollment, new student fees, tapping private donors—before campus and system leadership consider whether funding priorities need to change.

This inaction is an issue of incentives. The University of California is a complex $46 Billion business. At times, the bottom line pulls resources in a direction that aligns with students’ outcomes. Often, it is one or the other. When it comes to food, housing, childcare, and more, students’ needs have changed, but institutional incentives have stayed the same. This is true across higher education. Colleges opened their doors to a more diverse student body, then failed to provide them with equal opportunity.

Various states have attempted to adjust colleges’ incentives by tying state funding to students’ outcomes, but the results have been mixed at best. However, state funding is only part of higher education’s budget. Along with the benefits already discussed, informed enrollment attempts to tie tuition to students’ outcomes.

The University of California is in a unique position to make this a reality. Any UC campus is decades ahead of most schools when it comes to supporting students’ basic needs. In a transparent market for higher education, the UC system comes out on top, making them one of the few institutions in higher education that could benefit from informed enrollment.

Moreover, a change from the University of California wouldn’t go unnoticed by the rest of higher education. In the Fall of 2022, the UC system received over 250,000 applicants. If the UC system started to reevaluate their outreach to potential students, there would be an immense pressure for other institutions of higher education to do the same.

While some of my friends and classmates don’t know where their next meal will come from, others take unpaid internships. While parenting students slip out of class early to pick up their kids, others stay late to talk with professors. While some students go to football games, others drop out with debt they can’t pay back. From graduation rates and academic performance to mental and physical health, basic needs security plays a massive role in student outcomes.

John Luke Piepgras

Student at University of California, Los Angeles

Pre-college outreach was even mentioned in the UC’s 2020 basic needs strategy. Unfortunately, the implementation has been limited. UCLA still makes no mention of basic needs on their admissions or financial aid websites. The same is true for the system-wide admissions website. If campuses do include basic needs information, it is normally difficult to find. (UC Berkeley is a notable exception.) Without a standardized approach, it is impossible for students to weigh their options.

When I look at my university, I see one that is significantly ahead when it comes to supporting students’ basic needs. UCLA also has a ways to go until they figure out what they owe their students. Informed enrollment is a necessary first step in making sure students can express what they need from their colleges.