This page describes the rules for the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF). It is part of the report The State of State Choices: A national landscape analysis of postsecondary eligibility restrictions and opportunities in SNAP, CCDF, and TANF. Click here to return to the previous page, or continue reading below.

Introduction and Background on CCDF and Higher Education

Access to affordable, quality, and consistent child care is essential for all parents, especially for the one-in-five students who are balancing parenting and their postsecondary education.[1] A large share of parenting students are mothers and women of color. According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, nearly one-third of Black women, one-quarter of Indigenous women, and one-sixth of Latina women enrolled in higher education are single mothers.[2] Unfortunately, many parents cannot afford child care for their children and are experiencing high levels of basic needs insecurity. In the fall of 2020, 70% of parenting students experienced basic needs insecurity, compared to 55% among non-parenting students.[3] Nearly all Black and Latine single parenting students reported experiencing food or housing insecurity in the fall of 2020.[4] The Hope Center survey also found that Black fathers working towards their degree do not get significant support and face considerable challenges accessing to public benefits like food and child care assistance.[5]

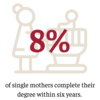

Financial burdens on parenting students, including the cost of child care, have only worsened in recent years. Prior to the pandemic, surveys showed that about 3 in 4 students found child care unaffordable.[6] A lack of affordable child care further strains students’ basic economic security, reducing their ability to persist and complete their degree or credential. Only 8% of all single mothers complete their degree within six years, compared to 49% of women without children.[7]

Addressing equity in college retention and completion requires meeting the needs of parenting students. However, parenting students have traditionally received less attention and support than students without children. For example, the federal Integrated Postsecondary Educational Data System (IPEDS), as well as most colleges and universities, do not identify parenting students or measure their outcomes as a specific population. Due to a lack of data about parenting students and their unique needs, this critical population is often ignored.[8] Failing to assess the needs of parenting students means colleges and policymakers cannot address critical barriers that parenting students face within their journey towards college completion. Only a limited number of states and systems of higher education require colleges to collect data on parenting students and they collect it in different ways.[9]

The Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), originally authorized as the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG),[10] is the primary source of federal funding for child care assistance. CCDF provides child care subsidies for families with low incomes while parents participate in eligible activities such as working or attending school. As a federal block grant, CCDF allows states to use a wide range of federal funds to make quality child care affordable for qualifying families. Nearly 1.5 million children receive a CCDF child care subsidy every month.[11]

CCDF as it is known today was created by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 and allocates child care assistance to states.[12] Since its inception, low investments in the system have failed to meet the need, even for the most vulnerable children. Due to limited funds, not all families with low incomes receive assistance, leaving CCDF to serve only 1 in 7 eligible children.[13] During the 2014 reauthorization of CCDF, the goals of the program were expanded to reflect the need to increase the quality of child care programs and support early child development and learning, as well as expand access to more families.[14]

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provided tens of billions of dollars to CCDF on top of more modest funding under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. This funding came after nationwide child care business closures fueled an already growing concern about affordability in the child care sector. However, that emergency funding has now expired, leaving the fate of child care support in doubt.[15]

CCDF Eligibility Requirements

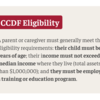

For families seeking child care assistance under CCDF, a parent or caregiver must generally meet three federal eligibility requirements:[16]

- their child must be younger than 13 years of age;

- their income must not exceed 85% of the state’s median income where they live (total assets must also be less than $1,000,000);

- they must be employed or enrolled in a training or education program.[17]

Each state has the flexibility to design income and other eligibility requirements within these federal parameters, which results in a wide variation in CCDF programs across the country. A GAO report found that state flexibility has led to fewer families qualifying for subsidies under state eligibility rules, as most states have used this power to set their income limits far below the federal maximum,[18] in part to ration the inadequate federal funding in the program. State policy choices, combined with limited funding, have led to a declining number of participants who are engaged in education or training.[19],[20]

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) notes that out of 13.5 million children eligible for CCDF support under federal rules, only 8.7 million qualified under state rules and only 1.9 million received subsidies.[21] Not only does this showcase how many qualifying families don’t receive assistance, but it also shows the role that both funding and state decisions play in limiting access to child care subsidies through stricter eligibility rules.

CCDF: Variation in State Rules Can Limit Benefits

In addition to the federal eligibility criteria for CCDF, some states have imposed restrictive eligibility requirements on parenting students, while others have attempted to open access to parenting students. States must submit plans to the HHS Office of Child Care every three years outlining how they will administer their program. We reviewed public CCDF state plans for fiscal years 2022-2024 and alongside some state manuals to better understand eligibility requirements and restrictions for parenting students.[22]

Specifically, some states have imposed work requirements on students, placed limits on the length of time students can remain enrolled in education and training programs, required academic progress, and even restricted the types of programs and degrees that parenting students are allowed to pursue. These barriers impede access for parenting students. A comprehensive set of materials on CCDF rules can be found in the state-by-state map below.[23]

Work Requirements

Some states require parenting students to be working full or part-time while attending school. Parenting students face the difficult challenge of not only going to class, studying, and caring for their children but also finding time to work.

Research has shown that combining schooling with more than 15 hours per week of work leads to lower persistence and graduation rates.[24] A recent survey of three years of community college “stop-outs” found that the most common reason that students said they left their program was that they “had to work,” at 49% of respondents.[25]

States that currently impose work requirements on parenting students should reconsider these barriers, as work requirements can have significant negative consequences for families that reduce the overall effectiveness of CCDF in supporting economic mobility. Parenting students are already improving their career prospects through education.

Each state plan determines whether parents qualify based on education and training participation alone (without additional minimum work requirements). There are eight states that require students to meet some sort of work requirement while pursuing an education or training program: Arizona, Kansas, Nevada, New York, Oregon (not including teen parents), Pennsylvania, Utah, and Wisconsin. Some states like Montana only require part-time students to meet a work requirement.

States determine how many hours a week a student must work or attend an education and training program to maintain eligibility. A total of 13 states do not specify the number of hours or course load requirements, but there are 18 states and the District of Columbia that require a minimum hour or course load requirement to meet the education or training eligibility. The most common requirements included attending school full-time, part-time, or participating in education for about 20 hours a week.

However, there are 11 states (Colorado, Hawaii, Indiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Vermont, and Virginia) that do not have a minimum hour requirement for the time spent in education or training programs, which gives students the most flexibility in how they manage their time.

Allowable Programs of Study

States also define what is considered an eligible “job training” or “education” program under which a parent can receive CCDF. Most states included some type of information on allowable programs and degrees. Of these, at least 25 states clearly allow parents to pursue a degree or program up to a bachelor’s degree. Three states (California, Tennessee, and Texas) explicitly allow students to obtain up to a graduate degree while receiving CCDF, although they may have a time or participation limit that we were not able to determine.

On the other hand, some states like Washington limit education to an associate degree, while New Hampshire limits it to an associate degree for families not receiving assistance through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. Some states, like Delaware, only allow postsecondary education to qualify for participants who are also simultaneously enrolled in TANF or SNAP E&T.

By limiting programs and degrees, states increase complexity and reduce the available pathways toward a credential for parenting students.

Time Limits

On top of limiting parents to specific programs, states can also place time limits for how long a parent can pursue an education and training program. Five states have a time limit of 24 months (2 years): Iowa, Kansas, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wisconsin. Washington D.C. places this limit only on non-degree programs, such as certificate programs. Idaho’s time limit is up to 48 months, while Rhode Island allows less than one year of education for income-eligible families. North Carolina allows up to 20 months. However, California and Colorado allow parenting students to enroll in the educational program for a longer period of time—at six and four years, respectively.

Because parenting students may need to extend their years of education given their competing family and work responsibilities, short time limits could have the effect of cutting off parenting students from needed assistance well before they can finish their program and increase the chances they drop out of school.

Academic Progress

Lastly, states can also make a parent's time within an education or training activity even more demanding if they require parents to meet an academic progress requirement or do not consider study and travel time as countable hours towards their activity requirements and child care needs. Studies show that grade point average or academic requirements, like Satisfactory Academic Requirements (SAP), can be burdensome for low-income students and those who face substantial life responsibilities, including child care. Conditioning students’ financial aid and other supports for their basic needs on GPA and similar requirements is counterproductive and inequitable.[26]

There are six states that specify that a parent must “maintain satisfactory progress with their university” or meet certain academic requirements. Of those, two (Kansas and West Virginia) specify that a parent must maintain a grade point average of 2.0 to showcase satisfactory standing, while the other four states do not define this further.

Additionally, 39 states include information about how travel and study time factor into maintaining eligibility for child care subsidies. Some of these states recognize that study time for classes, as well as the time it takes students to travel to and from school or child care centers, is a significant time component to a parent’s day and should be considered as such. Yet, these 39 states varied in how these hours are implemented into their activity hours, as illustrated in the table in the state-by-state map below. Some states measure travel time daily, while others offer up to five hours per week or twelve hours per month, though in many states the language is more vague and restricted to “reasonable” travel times, for example. Two states, Kentucky and West Virginia, specify that travel time does not count toward hours for the eligibility activity.

CCDF Recommendations for State Policymakers

With more parenting students struggling to meet their family’s basic needs while continuing their education, a major increase in federal and state investments is needed to support this population. One way to support parenting students is by granting them access to CCDF subsidies.

Through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), the HHS Administration for Children and Families received nearly $50 billion dollars to state, territory, and tribal CCDF programs, the HHS Administration for Children and Families received nearly $50 billion dollars to state, territory, and tribal CCDF programs.[27] These funds were able to help provide funding to services like child care and support parents and providers disrupted by the pandemic.[28] The White House estimates the funds helped keep 200,000 child care providers open to as many as 9.5 million students.[29] However, with these federal funds now expired, child care providers and the CCDF program are again struggling to meet the significant demand for child care. Furthermore, parenting students are contending with greater everyday expenses due to inflation and higher costs of child care.

While consistent federal support is needed to ensure parenting students who need it have access to affordable child care, states can play a vital role in increasing parenting students’ retention and completion by leveraging state rules to support these students better. States can best support parenting students by adopting the following recommendations and best practices for CCDF:

- Allow education and training as a stand-alone eligible activity with minimal red tape: Most states allow parents to receive CCDF subsidies by participating in education and training without also having to work simultaneously. Still, not all of these states do so in a flexible manner. Most parents who attend school already have numerous responsibilities and should not have to worry about meeting additional work or education hours or whether their specific combination of credit hours and work hours will satisfy the eligibility requirements to get help with child care. Hours can fluctuate and are often outside the student’s control. States that require work in addition to educational hours for CCDF should eliminate these rules to avoid hurting a parent's chance of completing their educational program. In addition, 11 states create flexibility for parenting students by not setting a minimum hour or credit requirement, which other states should emulate.

- Expand allowable programs to include at least bachelor’s degree programs: As mentioned, some states still do not allow parents to pursue any education or training above an associate degree while receiving CCDF. States that place limitations on educational programs are failing to expand their citizens’ economic opportunities and maintain their workforce competitiveness. All students should be able to obtain at least a bachelor's degree while receiving CCDF, and ideally, a graduate and professional degree.

- Maximize support for parenting students: To receive child care subsidies, a parenting student may face an eligibility time limit, be monitored for academic progress, and be unable to count any of their coursework or transportation time towards their activity hours or child care need. These rules can significantly influence a parenting student's journey in college, but there are very few states that transparently disclose information on their policies all three components. States should be more transparent about their rules. Most importantly, they should maximize the federal flexibility to support parenting students by removing these barriers altogether. States have the authority to remove time limits and grade point average requirements and include study and travel time in eligible activity requirements.

References for the state-by-state map can be found here.

Click here to continue reading about the rules for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) as part of The State of State Choices: A national landscape analysis of postsecondary eligibility restrictions and opportunities in SNAP, CCDF, and TANF. Click here to read about the rules for the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) program.

References

[1] Reichlin Cruse, L., Holtzman, T., Gault, B., Croom, D. & Polk, P. (2019a, April). Parents in college by the numbers. Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

[2] Reichlin Cruse, L., Milli, J., Contreras-Mendez, S., Holtzman, T., & Gault, B. (2019b). Investing in single mothers’ higher education: National and state estimates of the costs and benefits of single mothers’ educational attainment to individuals, families, and society. Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

[3] The Hope Center at Temple University. (2021). The Hope Center Survey 2021: basic needs insecurity during the ongoing pandemic.

[4] Kienzl, G., Hu, P., Caccavella, A., & Goldrick-Rab, S. (2022, February). Parenting while in college: Racial disparities in basic needs insecurity during the pandemic. The Hope Center at Temple University.

[5] Kienzl, G., Hu, P., Caccavella, A., & Goldrick-Rab, S. (2022, February). Parenting while in college: Racial disparities in basic needs insecurity during the pandemic. The Hope Center at Temple University.

[6] Goldrick-Rab, S., Welton, C., and Coca, V. (2020, May). Parenting while in college: Basic needs insecurity among students with children.

[7] Reichlin Cruse et al., (2019b).

[8] Goldrick-Rab, S., Welton, C., and Coca, V. (2020, May).

[9] Gault, B., Holtzman, T., & Reichlin Cruse, L. (2020). Understanding the student parent experience: The need for improved data collection on parent status in higher education. Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

[10] Given we examined the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) state plans for this research, the CCDF acronym will be used throughout the paper for consistency, rather than the Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG). The CCDF program is funded every year and authorized by the CCDBG Act.

[11] Office of Child Care. (2022). FY 2020 preliminary data table 1 - Average monthly adjusted number of families and children served. An Office of the Administration for Children & Families. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

[12] Child Care Technical Assistance Network. (n.d.). History and purposes of CCDBG and CCDF. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

[13] Chien, N. (2021). Factsheet: Estimates of child care eligibility & receipt for fiscal year 2018. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning & Evaluation.

[14] Child Care Technical Assistance Network. (n.d.).

[15] Gomez, Rebecca. (2023, September). Opinion: Federal funding for child care is about to fall off a cliff. Why that’s a disaster. Los Angeles Times.

[16] Citizenship status is a federal requirement, but only applies to the child for whom the subsidy is provided, and not the parents of the child.

[17] Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. (2021). Subpart C - Eligibility for Services § 98.20 A child's eligibility for child care services. National Archives.

[18] GAO. (2021). Child care: Subsidy eligibility and receipt, and wait lists. Government Accountability Office.

[19] Office of Child Care. (2022). FY 2020 preliminary data table 10 - reasons for receiving care, average monthly percentage of families. An Office of the Administration for Children and Families. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

[20] Adams, G., Giannarelli, L.,Sick, N., Dwyer, K. (2022). Implications of providing child care assistance to parents In education and training. Work Rise Network.

[21] The 1.9 million children who received subsidies came from CCDF and other related government funding streams. See: Chien, 2021.

[22] Information included applied to both single and two-parent households, unless specified in footnotes.

[23] For information on previous years, IWPR’s “Child Care for Parents in College: A State-by-State Assessment” covers 2016-18 CCDF state plans. For more information on state variations beyond education activity requirements, check out “CCDF Policies Database 2019 Book of Tables”.

[24] ACT Center for Equity for Learning. (2017, August). Who does work work for? Understanding equity in working learner college and career success.

[25] Nguyen, S. & Cheche, O. (2024, February). Enrollment at community colleges might improve, but challenges remain for students. New America.

[26] John Burton Advocates for Youth. (2021, July). The overlooked obstacle: How satisfactory academic progress policies impede student success and equity.

[27] Administration for Children and Families. (2022, October). American Rescue Plan. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

[28] Administration for Children and Families. (2022, October).

[29] The White House. (2022, October 21). Fact sheet: American Rescue Plan funds provided a critical lifeline to 200,000 child care providers – Helping millions of families to work.

[30] Alaska’s manual specifies that the monthly maximum allowable coverage for educational activities is a full time month regardless of education activities. Study time was also found in the manual.

[31] More time (up to 1.5 hours) may be allowed for parents who travel more than 30 miles to their activity or utilizes public transportation.

[32] Education and training, including college or trade/vocational activities, are allowed as long as the parent is working a monthly average of 20 hours a week.

[33] If a student participates in study groups, lab experience, outside class study or homework, these hours may be included in the number of child care assistance; parents are authorized up to 50 hours of child care assistance per week.

[34] Countable education includes postsecondary education leading to a degree or certification. A parent must also be participating in a SNAP E&T program or TANF E&T program.

[35] A student attending 20 hours per week is eligible. Additionally, a student can be enrolled in a full-time undergraduate program (min 12 credit hours); or enrolled in a part-time undergraduate program and employed to meet the hour requirement. When determining participation hours, one credit hour equals one hour countable towards the requirement.

[36] Two-parent families must complete at least 40 hours a week. The hours of child care depend on a parent’s participation in their educational activities. Additionally, some TANF recipients may not be subject to the 20 hour requirement.

[37] Associate degrees allowed include Associate of Arts and Associate of Science; Bachelor degrees allowed include Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science programs.

[38] Parents 21 years or older must meet a weekly 24-hour requirement with a combination of employment or full time or part time education. Parents under 20 years of age are not subject to the 24-hour requirement. For more information, the state manual is also a great resource: https://caps.decal.ga.gov/assets/downloads/CAPS/0-CAPS_Policy-Manual.pdf

[39] The associate and bachelor’s degree programs must be part of a HOPE eligible institution.

[40] Travel time is included when determining the hourly range of need for care; they specify 86 or more hours per month for full time care or 1-85 hours per month for part time care.

[41] To receive child care benefits for advanced degrees, they must be paired with a qualifying activity.

[42] There is no minimum hour requirement for work, which could also apply to the education component. State plan does not specify.

[43] When determining the time limit, a fiscal month will be used rather than a calendar month, so the time limit begins at the start of classes. High School education, GED, or ESL does not count towards the time limit.

[44] The occupation must be listed in the Occupational Outlook Handbook and must be skill specific or create greater earning potential. Occupations that do not must receive an approval.

[45] The 20-hour requirement can be a result of education and job training with a combination of work hours. Work may include unpaid work in regard to a higher education activity or work-study. For two-parent households, a minimum of 40 hours per week (one of those parents not working less than 5 hours).

[46] Full-time will be considered as 12 credit hours or more; part-time will be considered as 12 credit hours or less and the credit hours will be multiplied by 2.5 to establish child care needs. Similarly, participating for 30 or more hours per week in an activity is considered a full-time service need, whereas participating for at least 20 hours is considered a part-time service need. Work-study required practical and clinical experiences (including student teaching or internships) are counted as hours of employment.

[47] Parents must be meeting a minimum of 20 hours requirement and be the one to take the child to and from child care for travel time to qualify.

[48] Under the working component, Michigan does not require a minimum number of hours per week, which could be applicable for the education component as well. State plan is not explicit.

[49] Additional travel time can be requested, and they also allow time for meals or breaks.

[50] Non-TANF parents can pursue educational programs, including remedial or basic education or ESL and a program leading to a Bachelor’s degree. For TANF parents, they can participate in education and job training programs that are approved within their TANF Employment Plan.

[51] If a parent is enrolled full-time (12 hours or more), child care is automatically authorized for up to 23 full-time units. If a parent is attending evening classes, care will be authorized for evenings and weekends. Additionally, child care can continue if travel time prevents parents from returning to activity in a timely manner. For more information on child care hours, see state plan.

[52] A single parent attending school or a training program full-time meets the activity requirements. However, a single parent attending part-timemust work for a minimum of 40 hours per month. For two parents, they must work a minimum of 120 hours per month with either/or both parents working, attending school or a training program, unless they are both full-time in an education or training program.

[53] This only applied to parents in an accredited community college, college, or university program. Parents in “job training programs” (vocational school, GED preparation, or an employment preparation program) must meet 20 hours a week without compensation; if they receive compensation, it is considered a “working” component.

[54] Non-TANF parents can only pursue a degree up to an associate degree level. TANF parents who are not receiving NHEP, can pursue an associate and bachelor’s degree.

[55] Parents must be enrolled full-time for a total of at least 12 credits hours (9 credit hours during the summer term) at a college, university, or other education facility.

[56] Parents will get reimbursed for as little as 5 hours or less per week.

[57] To pursue an associate or bachelor’s degree, a participant must meet the following: participate in non-subsidized employment for at least 17 ½ hours per week, demonstrate the program will lead to improved earning and demonstrate they can successfully complete the program.

[58] Education hours are determined by multiplying the number of enrolled credit hours by 2 or actual hours of attendance when the program is not based on credit hours.

[59] Child care may be allowable past 24 hours when need is shown through their hours of employment, training, or education.

[60] Programs must qualify for federal financial aid from the U.S. Department of Education or other federal or state education funds. This applies for Non-TANF participants. TANF participants are allowed any activity approved in their TANF Work Plan.

[61] Travel time is included when calculating child care, as well as actual classroom attendance and any other activities required to maintain a course or scholarship. Additionally, for working parents, sleep time is also considered employment if the parent works nights and has an alternative care provider during work hours and needs child care to sleep during the day.

[62] Teen parents do not have a work requirement and qualify on education alone. The parent must have been eligible for ERDC child care assistance based on their employment activity; working parents receive a max of 20 hours a week for class time. Education hours cannot exceed the approved work hour or a combined total of 50 authorized hours per week or 215 per month (20 hours of work, 20 hours of school and 10 for travel).

[63] All non-TANF participants must meet a total of 20 hours of work a week, however, education or a training program can qualify for 10 of those hours. TANF participant eligibility and requirements are determined by the agent or caseworker who determined their TANF benefits. This does not apply to teen parents.

[64] For income eligible families (below 180% of the federal poverty level), they must participate for at least 20 hours a week in training programs (including internships, on-the-job training job readiness programs) funded by the Governor's Workforce Board or state agencies as part of the coordinated program system. State plan does not mention specific postsecondary education programs. For categorical eligible families, they are authorized to receive services if they participate in the education and training component, approved by their TANF Employment Plan.

[65] TANF participants may not need to meet the 15-hour requirement.

[66] This is for non-TANF families. They can also meet this requirement by combining work and school hours for a total of at least 80 hours a month. TANF families also qualify for child care assistance but must meet requirements set by their TANF Employment Plan.

[67] Parents with school aged children have their supplemental hours calculated at 30% of a parent's total weekly hours (employment, training, or school) and are allowed 35 hours/month of vacation/in-service hours.

[68] If enrolled part-time, participants must also be employed and meet a combined 30 hours per week. This pertains to non-TANF child care. In two-parent households, one parent must be working for 30 hours a week, while the other attends school full-time or part-time. If both enrolled in school, one must be attending full-time. For TANF participants receiving cash assistance, any TANF-countable activity qualifies as work, but they must meet the 30-hour activity requirement.

[69] Participants pursuing a graduate program may count 6 hours towards the work requirement and may add up to 2 hours of study time for a total of 8 hours towards the work requirement.

[70] The hour requirements could be in combination of work, job training, or educational activities for a one-parent household and 50 hours per week for a two-parent household. Each credit hour course counts as 3 hours of activity per week. State plan states this is for at-risk and former Choices child care.

[71] Texas considers education to be defined to include a postsecondary degree from an institution of higher education. Verified with a local state office that this includes up to a graduate degree.

[72] In two-parent households, one parent must work an average of 15 hours per week, while the other works an average of 30 hours a week.

[73] Each class credit is worth one hour of child care. A participant can participate in an education program that will most likely lead to employment within one year of program completion.

[74] Education activities must correlate to a participant’s employment goals. A full day of care up to 12 hours may be authorized for each class day for parents.

[75] Non-TANF or non-BFET families must be enrolled full-time in a community college, technical college, or tribal college. Enrolled in university programs not allowed. Part-time enrollment is acceptable for vocational education, adult basic education, and ESL, but must be in combination witha minimum of 20 hours per week or a minimum of 16 hours per week in state or federal work-study.

[76] The job training component allows participants to attend technical college or other courses of study. The state plan does mention any other postsecondary institutions as an allowable activity. Participation in Wisconsin’s W-2 TANF program or the FoodShare Employment and Training program is also allowed.

[77] Information taken from the child care subsidy manual, as a state plan could not be identified. Manual does not include information on activity requirements. https://dfs.wyo.gov/about/policy-manuals/child-care-subsidy-policy-manual/

[78] For a parent to pursue a postsecondary degree, they cannot exceed the following time limitations: 3 years for an associate degree and 6 years for a baccalaureate degree (only applies when they were not working an average of less than 30 hours per week while attending class). If employed more than 30 hours per week, the time limit extends to 5 years for an associate and 8 years for a baccalaureate degree.