Finding affordable and reliable child care in North Carolina has become nearly impossible. Due to the COVID pandemic, the state now has 3,120 fewer child care workers than it should have. A new report says the crisis may soon get much worse: the parents of as many as 155,000 kids could lose their child care as federal pandemic aid begins to dry up this fall.

Without enough workers to staff child care centers, families can’t find adequate care that is accessible from their home, work, and school. Parents in college face an even more daunting task—juggling courses, exams, and homework while caring for their families. If parenting students can’t get the support they need to get a degree or credential, the state could face even more dire and widespread workforce challenges.

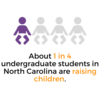

About one in four (23%) undergraduate students in North Carolina are raising children. That’s more than 136,000 parenting students in the state that need support. Investing in parenting students benefits our economy, workforce, and communities. Single mothers in the state who graduate with an associate degree are 44% less likely to live in poverty and earn almost $285,000 more over their lifetime—contributing more than $73,000 in additional federal and state tax revenue.

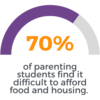

Despite their potential, parenting students face countless obstacles to obtaining a degree or credential. The Hope Center at Temple University found that parenting students experience disproportionate levels of basic needs insecurity compared to students without children, with 70% of parenting students finding it difficult to afford food and housing. It’s no wonder why. Infant care in North Carolina costs around $790 per month—nearly four times more than in-state tuition and fees at the state’s community colleges.

The first step toward addressing this crisis is quantifying the problem. North Carolina should require colleges to collect data on the exact number of parenting students at each campus and how many finish their degrees. The state should emulate others like Washington, which collects data on parenting students to help make a case for more resources and to help institutions improve their services. Parenting students need infant and toddler care, flexible evening and weekend hours, and a welcoming campus environment with family-friendly spaces and points of contact to help them navigate a confusing web of campus and community resources—all of which require good data to be effective.

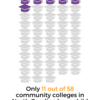

Governor Cooper recently proposed that the state invest $1.5 billion in new funding in child care and early education—including $11 million for community colleges to expand on-campus child care for parenting students. The call to expand child care comes at a critical time, as many child care centers have closed, especially at community colleges where a larger share of parenting students are enrolled. Just 11 out of 58 community colleges in North Carolina have on-campus child care today. That means most students must fight for child care slots at expensive private centers with substantial backlogs and waitlists. Bypassing these waitlists will help parenting students complete a degree or credential and enter the workforce.

The Legislature recently proposed a $1.2 million increase for the Community College Child Care Grant program. This program helps parenting students at the state’s community colleges find affordable slots for their children. Unfortunately, the program has only been able to serve a fraction of the parenting students who need assistance with child care, but the new investment will help. The state should ensure the program’s size and scope are designed to meet the needs of parenting students.

The state can also draw on federal funds to help more parents. The NC Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) subsidizes child care for families with low incomes that participate in a job or education program. But the state has not maximized eligibility for this program to support parenting students. For example, students are specifically limited to 20 months of support under CCDF, making it nearly impossible for parenting students to stay eligible for care the total time they’re enrolled in school (a minimum of 24 months for an associate degree or 48 months for a bachelor’s degree, assuming full-time enrollment, which is a challenge for many parents to sustain). Most states have no time limit on CCDF at all—including South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. North Carolina should join its neighbors in expanding access to more parenting students by removing these time limits on students.

Colleges can also apply for federal grants from the U.S. Department of Education’s Child Care Access Means Parents in School (CCAMPIS) program to create or expand their on-campus child care services. This program has been significantly expanded, but North Carolina hasn’t applied for its fair share. Only seven out of 136 colleges and universities in the state have received a CCAMPIS grant, and just three of the state’s 58 community colleges have been awarded funds. More colleges should compete for this valuable funding source.

While policymakers consider other ways to fix our child care crisis, institutions of higher education can also make a difference for their students. At UNC Chapel Hill, students can receive scholarships to cover a portion of child care costs. North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University was awarded a $75,000 grant from Ascend at the Aspen Institute to support their parenting students by increasing access to child care, creating lactation spaces and support groups, and referring students to other resources to meet their basic needs.

Parenting students are an essential part of our communities and our workforce. They are highly motivated but are also most likely to stop out of college due to inadequate support. The Governor and Legislature’s proposed investments in child care are a good start to help increase child care access for parenting students. The state should go even further by collecting data on parenting students and making CCDF more flexible. Investing in parenting students is vital for North Carolina’s workforce, and we must ensure they have the support they need to finish college and take care of their families.

Leslie Rios recently served as a Policy Associate with The Hope Center at Temple University. She is now a Senior Policy Associate at The Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS).