More than five million college students, including more than one-in-five undergraduate students (22 percent) and almost one-in-three graduate students (31 percent), are attending college while raising dependent children of their own.[1] These students are required to make daily financial and time sacrifices to meet the needs of their families and simultaneously succeed in school—all while often holding down a job. Yet far too frequently, the rising cost of attending college—including tuition, child care, housing, food, and more—remains far too great. As a result, parenting students, particularly Black, Asian, and Latine parenting students, face exceedingly high rates of basic needs insecurity compared to students without children, and often drop out of college at higher rates.

Ensuring that families have access to affordable, high-quality child care is essential in fixing the college affordability crisis, reducing basic needs insecurity, and even eliminating student debt. No student can be reasonably expected to afford child care prices that average more than $10,000 nationally, and exceed tuition costs at public 4-year colleges in many states. And indeed, according to The Hope Center's most recent survey of roughly 23,000 parenting students, 70% report that their child care arrangement is not affordable. Unsurprisingly, parenting students also graduate with far more debt than their peers. Despite this, and even with bipartisan attention on the need for greater child care investments, there are precious few ways that federal policy helps parenting students meet this crucial need.

The beginning of the 118th Congress is a time to change that.

There are at least three programs with the infrastructure to deliver financial assistance to parenting students and increase the supply of affordable child care options on- and off-campus: The Child Care Access Means Parents in School (CCAMPIS) program, the Child Tax Credit (CTC), and the Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG). Unfortunately, the effectiveness of each of these programs is compromised by a lack of funding, overly complex design, or expiration of some of their most promising features. But with enough political will, Congress could commit to ensuring that parenting students have an equitable shot at navigating their degree program, which would have countless benefits for both students and society at large.

Improve and Expand CCAMPIS

For colleges and universities, the time and investment required to maintain adequate, quality on-campus child care can be overwhelming. To help defray some of the costs, Congress allocates funding for the Child Care Access Means Parents in School (CCAMPIS) program, designed to provide child care for low-income parenting students either on campus or through a community partner.

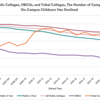

CCAMPIS remains the only program dedicated to campus child care, and for those who can take advantage of it, CCAMPIS participation is associated with higher retention, completion, and academic performance. Yet despite increases in recent years, the program remains funded at a meager level relative to the need; only around 300 institutions received CCAMPIS grants last year, and estimates from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research suggest that only 1% of potentially eligible students are served. This is especially concerning given that the share of colleges with on-campus child care has declined over the past two decades, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: The Hope Center’s calculations from the U.S. Department of Education Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

At public colleges, only 42.9% of campuses had on-campus child care in 2021-22, down from nearly 60% in 2004. And only 1-in-5 HBCUs can offer on-campus child care, despite nearly 80% of parenting students at HBCUs reporting that child care is unaffordable.

In the end-of-year government funding bill passed by Congress in December 2022, CCAMPIS received a modest $10 million boost, to $75 million for Fiscal Year 2023. At this funding level, CCAMPIS funding is woefully inadequate; the program is funded at only about 1/6th of the level that advocates have called for to better meet the needs of parenting students.

Further, given the small amount of the average CCAMPIS award (about $273,000), many institutions have still faced substantial funding needs, in part due to an artificially low cap on the amount that any campus can be awarded (which was equal to 3% of the total amount of Federal Pell Grant funds awarded to students at the institution). Rural-serving institutions (RSIs) are underrepresented in CCAMPIS grants as well. An analysis of the most recent list of CCAMPIS recipients shows that fewer than a quarter of grantees qualify as rural-serving institutions (despite nearly half of all public colleges being designated as rural-serving).

Fortunately, Congress recently included language in the government funding bill to allow for larger CCAMPIS grants that are “reflective of the costs to provide high-quality child care to student parents.”, and to target limited funds based on the number of Pell Grant recipients (rather than total dollars) at each institution. This should have the effect of increasing the maximum grant for some institutions, and particularly institutions enrolling more students with low incomes, allowing them to offer services to more students on a consistent basis. Yet without a substantial increase in CCAMPIS appropriations, too many colleges–and students–will continue to receive little to no support.

Bring Back the Monthly Child Tax Credit

One of the highest-profile and celebrated pieces of the American Rescue Plan Act was the expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Not only did Congress expand eligibility to more families and increase the amount families could receive (up to $3,600), but it also disbursed half the benefit monthly between July and December of 2021. This, in effect, created a monthly child allowance for parents of up to $300 and an additional payment at tax time that reached over 60 million children nationwide. Consistent with research around the profound impact of child allowances and basic income, the monthly CTC led to a dramatic, and almost unheard of, reduction in poverty rates, as well as a reduction in food insecurity. CTC-eligible households were more likely to seek out professional skills and training than households that were not eligible, and many families – particularly Black and Latino families – were more likely to use funding on children’s educational and child care expenses.

For parenting students, the expanded CTC was particularly useful. The expansion ensured that families were eligible for the full credit even if they had no or low earnings throughout the year, a particular boost for full-time students who may have modest wages from a part-time job, as well as low-income households who previously only qualified for a partial credit.

Yet, despite the program’s unmitigated success, Congress allowed the monthly expanded CTC to lapse at the end of 2021, reversing many of the gains on child poverty and taking away a vital resource to families and parenting students alike at the very moment that the cost of child care, living, and basic necessities increased dramatically.

Lawmakers toyed with the idea of bringing back the monthly CTC at the end of 2022, to no avail. And even then, some Congressional leaders insisted on adding an unnecessary and counterproductive work requirement to the monthly credit, even though there was no noticeable difference in employment between families who received the monthly CTC and those who did not. Adding a work requirement, particularly one that does not recognize enrollment in higher education as a qualifying activity, would lock out millions of parenting students from taking advantage. Instead, Congress should insist on bringing back the full monthly credit and ensure that those who were able to experience a profound, if temporary, respite from financial insecurity, can once again take advantage of it.

Reform the Child Care Development Fund to Address the Needs of Students

The Child Care Development Fund (CCDF), authorized by the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), is another main source of federal funding for providing child care subsidies to low-income families who work or attend school. CCDF funding flows to states, who distribute and administer their programs to eligible parents of children under 13 (those who are employed or participating in a training or education program and meet income eligibility). In 2020, an average of 1.49 million children were served through CCDF each month.

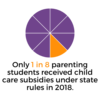

However, once again due to limited federal funding, CCDF fails to reach all eligible families, forcing states to make tradeoffs and maintain waitlists. Within broad federal parameters, states have broad flexibility in outlining how they will administer their program. States often set restrictive eligibility requirements, which results in varied and confusing state rules. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has reported that out of 12.8 million children who were eligible under federal rules, only 8.4 million qualified under state rules and only 1.9 million received subsidies. And only a fraction of parenting students ends up receiving child care subsidies under CCDF: In 2018, only 1 in 8 parenting students received child care subsidies under state rules. This is because states can set stricter initial income eligibility requirements that are far below the federal maximum and impose additional burdensome rules pertaining to parents pursuing education or training, among other program components. Several states have required work requirements for students, placed limitations on types of programs they can pursue, placed time limits restrictions, and required students to illustrate academic progress. These restrictions can harm a student’s ability to stay enrolled in college, as they already have numerous responsibilities on their plate. States should ensure they are maximizing federal eligibility to best support their parenting students.

Beyond encouraging states to remove harmful barriers, further investment is needed to support a larger number of families. During the year-end spending bill, the CCDF received a 30% increase from the previous year, a substantial increase. But this new investment won’t reach the parenting students that need assistancewithout a push from Congress and the Biden Administration to ensure more students are connected to the funds.

Not all states readily communicate the rules or availability of resources to students who need child care support, and CCDF is very rarely mentioned by campus leaders as a viable option or benefit to addressing the child care affordability crisis for students. At minimum, HHS should clarify and uplift best practices on expanding access to CCDF for parenting students, including encouraging states to prioritize funding for campus child care through CCDBG, allow education and training to stand alone as an eligible activity without needing to also meet work requirements, ensuring all students are eligible (including those who are enrolled in bachelor’s degree programs).

Addressing the Child Care Crisis is a Matter of Political Will

Few could argue that investments in parenting students aren’t likely to pay off for individuals, campuses, and communities. Without investment in these students and their basic needs, those who cannot afford child care will continue to avoid enrolling in a degree program, work more hours and jeopardize academic performance, drop out, or take on exceedingly large student debt. Programs like CCAMPIS, the CTC, and CCDF have all been the object of bipartisan affection, yet all of them suffer from a lack of investment to truly address this crisis.

At a time when college enrollment has flatlined, families face higher prices, and the cost of college continues to spiral, Congress and the Biden Administration have a fresh chance to provide some long-term relief for the 22% of undergraduate students, and 31 percent of graduate students, with dependent children.

[1] The percentages of parenting students are data pulled by the author from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study: 2016 Undergraduates (NPSAS:UG) and National Postsecondary Student Aid Study: 2016 Graduate Students (NPSAS:GR).